Biography of Clark

A version of this article by James J. Holmberg appeared in The Encyclopedia of Louisville:

William Clark, explorer, soldier, and government official, was born on August 1, 1770, at the Clark homestead in Caroline County, Virginia. He was the ninth of ten children and youngest of six sons of John and Ann (Rogers) Clark. Clark received some formal schooling in Virginia. When he was fourteen the family moved to Jefferson County, Kentucky, settling at “Mulberry Hill,” about three miles southeast of Louisville. William pursued a more “practical” education at this point, becoming proficient in surveying, cartography, wilderness living, and operating a plantation. By the time he reached twenty-one he was a planter, surveyor, frontiersman, and soldier. A military career seemed a natural occupation for Clark. All five of his older brothers had served in the Revolutionary War, including the “Hannibal of the West” George Rogers Clark, and two (John Jr. and Richard) had died in the service of their country. William grew up hearing tales of his brothers’ and their contemporaries’ military exploits. He might have served under his brother George in a 1786 militia expedition against the Wabash River Indians, but it is certain that he served in John Hardin’s 1789 expedition against the White River Indian towns, Charles Scott’s 1791 expedition against the Ouiatanon Indian towns, and assisted with the defense of the settlements against Indian attack. His abilities were recognized by his commanders and received praise.

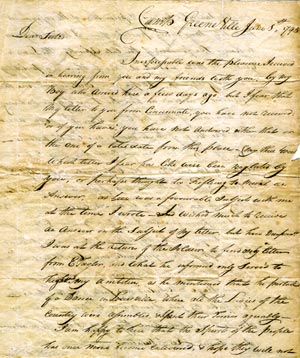

On March 7, 1792, he received a second lieutenant’s commission in the infantry of the regular army. Clark went on recruiting duty, and in September was assigned to the 4th Sub-legion of the U.S. Army. General Anthony Wayne was preparing a campaign against the Northwestern Indians in Ohio and Indiana at this time, and Clark served under his command for the next four years. In June 1793 Clark led a mission to the Chickasaw Bluffs (present Memphis, Tennessee) to bring arms and ammunition to the Chickasaw in order to keep them allied to the U.S. rather than defecting to the Spanish. In September 1793 Clark was placed in command of a rifle corps and during the winter of 1793-94 commanded a detachment at Vincennes. In the spring and summer of 1794, Wayne launched his campaign against the Indians. Clark was placed in command of a supply train and successfully defended it against an Indian attack. He commanded a rifle company in the American victory at Fallen Timbers in August and was present at the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. It was in late 1795 or early 1796 that he met and became friends with Meriwether Lewis, a junior officer under his command. The appeal of a military career had begun to fade for Clark and he decided to resign in order to pursue business opportunities, assist his brother George with his tangled legal and financial affairs, help run the family’s plantation, and due to poor health. Before resigning he went on one more mission southward; this time to New Madrid, where he protested to Spanish officials about the fortification of Chickasaw Bluffs. Clark resigned his commission as a first lieutenant of infantry on July 1, 1796, and returned home to “Mulberry Hill.” He was frustrated in his plans for a mercantile career, largely due to family responsibilities, and particularly due to brother George’s tangled affairs. For the next few years, he traveled thousands of miles on business, especially on behalf of his brother, visiting St. Louis, New Orleans, Baltimore, Washington, and Virginia. Much of what George Rogers Clark retained was due largely to his brother’s efforts. Clark continued an interest in military matters. On May 28, 1800, he was commissioned captain of a troop of cavalry in the Jefferson County militia, 33rd Regiment of Kentucky militia.

In July 1803 Clark received an invitation that changed his life and secured his place in history. His friend and former subordinate, Captain Meriwether Lewis, then private secretary to President Thomas Jefferson, invited Clark to join him as co-commander of an expedition to the Pacific Ocean. Clark accepted in July and began recruiting men in Louisville and Clarksville (where he had moved a few months earlier). On October 14, Lewis reached Louisville and on October 26, the co-commanders and the nucleus of the Corps of Discovery set off down the Ohio on a journey lasting for the next three years. During that historic venture Clark played an important role in its success. He and Lewis complemented each other’s talents; he was an effective negotiator with Native Americans encountered; faithfully kept a journal; and almost invariably his practical, gregarious temperament served the expedition well.

Following the expedition’s September return to St. Louis, the captains’ continued on to Louisville, and eventually Washington. They were met with praise, and often banquets and balls, from St. Louis to Washington. On February 27, 1807, his resignation as a first lieutenant in the artillery (he had been denied the promised captain’s commission in the infantry, and instead received a second lieutenancy in the artillery and in February 1806 had been promoted to first lieutenant) was accepted. Jefferson’s proposal to secure a lt. colonel’s commission in the army for him was denied. Instead, as a reward for his services, he received a commission as brigadier general of the Louisiana Territory militia and was appointed chief Indian agent for the territory. Clark also received double pay for the period of the expedition and a 1,600-acre land grant. In September 1807 he supervised a fossil dig at Big Bone Lick in Boone County, Kentucky, for Thomas Jefferson.

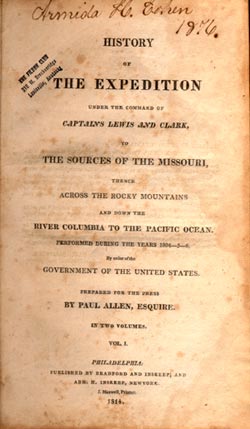

Clark settled permanently in St. Louis in June 1808 and was an important figure in Missouri affairs for the next thirty years. Within a couple of months of arriving, he traveled up the Missouri River east of present day Kansas City and established Fort Osage. Much of his time was occupied with government business, especially Indian affairs. He also acquired land and attempted to reap some of the benefits of commercial trade in the frontier town. Following the death of his close friend and partner in discovery Meriwether Lewis in October 1809, the task of publishing their expedition journals fell to him. Knowing that his strengths lay in other areas, he retained Nicholas Biddle to edit them. He answered extensive questions from Biddle and had expedition member George Shannon assist Biddle as necessary. They were published in 1814.

In 1813 Clark was appointed territorial governor of Missouri and retained the post until Missouri became a state. During the War of 1812, he organized the defense of Missouri and led an expedition up the Mississippi River to Prairie du Chein, where he built a fort. Due to the expiration of the militia’s enlistments, he was forced to return to St. Louis, and the garrison left behind later surrendered to the British. Both as governor of Missouri Territory and as superintendent of Indian affairs (a position he assumed as governor and retained after leaving that office) he negotiated frequently with Native American delegations from various tribes. He was well respected and trusted by the Indians, who called him the Red Headed Chief. While doing what he could for the Indians’ eventual acculturation and assimilation, he worked to extinguish their land claims and further open up the West for white settlement. Over the years he acquired a large collection of Native American and natural history artifacts that he displayed in his townhome, office, and country estate “Minoma.” He was defeated for governor of the state of Missouri in 1820. President Monroe appointed him surveyor general of Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas, 1824-25, and he founded Paducah, Kentucky, in 1827. His later years were marked by some financial difficulties and physical and mental decline, but he continued his habits of hospitality until his death. Clark died in St. Louis on September 1, 1838, and was buried on his nephew John O’Fallon’s estate “Athlone” in what his son Meriwether Lewis Clark identified as the “Font Hill” vault. His remains and those of other Clarks were reinterred in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis on October 23, 1860.

While in the East in 1807, Clark renewed his acquaintance with Judith (better known as Julia) Hancock (1791-1820) of Fincastle, Virginia. They married in Fincastle in January 1808. They had five children: Meriwether Lewis, William Preston, Mary Margaret, George Rogers Hancock, and John Julius. Julia Clark died at “Fotheringay,” the Hancock family estate in Montgomery County, Virginia, on June 27, 1820. Clark married her cousin Harriet Kennerly Radford (1788-1831), the widow of Dr. John Radford, on November 28, 1821, in St. Louis. They had two children: Jefferson Kearny and Edmund.

John Loos. “A Biography of William Clark, 1770-1813.” Ph.D. dissertation, Washington University, 1953; Jerome O. Steffen, William Clark: Jeffersonian Man on the Frontier (Norman 1977); James J. Holmberg. “William Clark.” In Christy H. Bond, Gateway Families (Boston 1994), 178-90. Louise Phelps Kellogg. “William Clark.” In Dictionary of American Biography (New York 1930) 4:141-44.

Since publication of the Encyclopedia two biographies of Clark have been published: William Clark and the Shaping of the West by Landon Y. Jones and Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark by William E. Foley.