William Clark’s letters to his “Dear Brother”

By James J. Holmberg

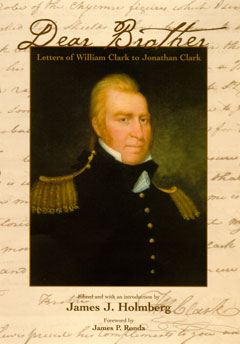

In September of 1792 famous explorer, William Clark began an extraordinary nineteen-year correspondence with his brother Jonathan Clark that continued until the latter’s death in 1811. These letters reveal William Clark on a more personal level than any other known source. They open a window not only to him as a person but to his world. The vast majority of the known letters – forty-six of them (a few others are at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin) – are in the collection of The Filson Historical Society in Louisville, Kentucky. It was my pleasure to edit these letters in Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark (Yale University Press, 2002).

In the nineteen years the letters span, William Clark rose from a young army officer serving on the frontier during the Indian wars of the 1790s to a territorial administrator on the edge of the frontier. In between was a crowded life full of activity, including the “Western trip” to the Pacific with his friend and co-leader Meriwether Lewis. Jonathan Clark was twenty years older than his youngest brother. Not only was he the archetypal “big brother” but he was also a father figure to his brother William. The younger Clark’s letters bear this out again and again. Assuring Jonathan that he wished him to “See & know all” and that he wrote to him “without reserve,” feeling “no restraint either in stile or grammar,” William’s letters are a priceless source of information about the man, his contemporaries, and his times. Among the letters are five previously unknown Lewis and Clark Expedition-date letters, including his first report home in December 1803 since pushing off from the Falls of the Ohio in October 1803 and his communication in April 1805 from Fort Mandan before setting off into a country that was “extencv and unexplored.” It is because of these letters that we know the reason for the alienation between Clark and his enslaved African American York and York’s sad post-expedition experience. These letters also reveal William’s reaction to Meriwether Lewis’s death and his belief that his friend had taken his own life. Whenever he received a report on Lewis in that fateful fall of 1809 he passed the news on to Jonathan. And there is much more in the letters – from observations on love and the joys of domestic life to Indian affairs and dueling. William’s letters to Jonathan provide a wonderful window to peer back into our past.

I first learned of this cache of William Clark letters in December 1988. I saw them for the first time on February 15, 1989. That day coincidentally was my birthday, and for a historian, especially someone who had grown up following parts of the Lewis and Clark Trail and reading about the explorers, what a present seeing those letters were! To hold in my hands these historic documents and to be reading the answers to questions that had bedeviled historians for some two hundred years was electrifying. Being familiar with available Lewis and Clark sources I knew these letters were not only unpublished but unknown. I decided at that moment that if I should have the opportunity I would edit the letters for publication. In 1990 the owners (descendants of Jonathan Clark) donated the letters to The Filson Historical Society and I began to edit them immediately. This personal project soon became a professional endeavor as well, supported by The Filson. Devoting a combination of days, nights, and weekends to the project as opportunity allowed that proverbial light at the end of the tunnel drew closer and brighter. In 1998 when the donors presented the bulk of the family papers to The Filson, four more William Clark letters were discovered. I suspected there may be additional letters in the collection and upon their discovery included them in the almost completed edition of William’s “Dear Brother” correspondence. The manuscript was accepted by Yale University Press and in 2002 Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark was published by Yale in association with The Filson.

We are fortunate that such letters have survived and can now be read and learned from today. They are pieces of our heritage and our nation’s collective memory. Every time we lose such a piece we lose something of our history and ourselves. Those who went before us – whether or not they are famous – help define who we are today. Like pieces of a puzzle or tiles in a mosaic, William Clark’s letters to his “Dear Brother” help create a more complete image and a better understanding of our nation’s heritage and who we are today.