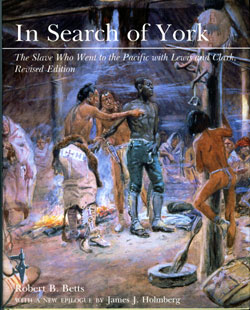

York of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

By James J. Holmberg

The America of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was a world of master and slave. It was York’s world, and it was William Clark’s world. Both were products of a slaveholding society. That society, with its beliefs and customs, shaped these two men. It helped make them who they were. Companions since small children, York and Clark grew up together. But because of the color of their skin, their positions in society were preordained. Their relationship with each other was defined. One was free and one was not. One was the master and one was the slave.

In recent years something of a Renaissance has occurred regarding interest in York. In recent years something of a Renaissance has occurred regarding interest in York. In recent years something of a Renaissance has occurred regarding interest in York. This is especially true during the 2003 to 2006 bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. There are a growing number of works in a variety of mediums dedicated to York that not only inform about him but serve to give substance to the experience of a slave from this period in America’s history. The vast majority of slaves lived lives that are lost to history. Their names are often not even known. York has not suffered that fate. Researchers and writers have revealed enough information about York to produce not only an excellent biography but to also make him one of the best-documented members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. York became the first African American to cross the United States from coast to coast. He is not only a famous African American, but a famous American as well.

Imagine York’s world. Think how it must have felt to be a slave. Your fate was not your own. Everything you had was dependent on your master. Your clothes, your food, your happiness, your family, and even your life all depended on the person that owned you. It is believed that York was owned by the Clark family since birth. His father was also named York. As York grew to manhood, his father became known as “Old York.” Old York was a trusted Clark family slave. He most likely was John Clark’s personal servant. His son served in the same capacity as John Clark’s son, William. The two boys grew up together. They played together and worked together. While still boys, York would have been formally assigned to William as his personal servant. This meant that York inhabited the upper level of the slave hierarchy. As a house slave, rather than a slave who worked in the fields, and as the personal servant of a prominent person, York would have enjoyed privileges that most slaves did not. But he was still a slave.

York was well traveled before going on the expedition. He came to Kentucky with the Clark family from Virginia in 1785. In the 1790s William Clark traveled widely east of the Mississippi while in the army and on business. York was often with him. In July 1803, Clark accepted his friend Meriwether Lewis’s invitation to serve as co-commander of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He then began recruiting the hunters and woodsmen who became the first permanent members of the Corps of Discovery.

Lewis and Clark knew the type of men who were needed on an expedition going into unexplored wilderness. Men with those skills lived on the Kentucky frontier. During the twenty year period that pioneers and Indians battled for control of Kentucky and the Ohio Valley, African Americans fought side by side with white pioneers. Their lives could depend on whether they could shoot, hunt, track, and scout. York grew up on the frontier. He had many of the same skills as those famous “Nine Young Men from Kentucky” of the Expedition. William Clark knew this and probably never had a doubt that York would accompany him on the expedition. Having just a servant along to make life on the journey easier was a luxury that couldn’t be afforded. York had the frontier skills that made him a valuable, contributing member of the expedition.

York did not disappoint the captains and his fellow explorers. He did everything that was expected of him on the expedition. In fact, he did more. Many of the American Indians encountered had never seen a black man before. They were amazed by York. The Indians believed that York had tremendous spiritual power. Lewis and Clark used this to their advantage. York became a way to impress the Indians and therefore help the expedition succeed. Imagine how York must have felt! York was a slave because of the color of his skin. He had been told his whole life that he was inferior to white people. He was not even an official member of the Corps of Discovery because of his status as a slave. And now, here he was, on an expedition to the Pacific Ocean whose hardships and dangers forged the diverse Corps into a team dedicated to its goal. Although York never would have completely escaped his position as a slave, he very much was one of the men – in many ways an equal. Add to this the fact that many Indians believed that York was superior to his white companions, and you can imagine how York must have felt. In November 1805 the captains took a poll of the Corps’ members about where to spend the winter. York’s opinion was valued enough that he was asked to voice it, and it was recorded, along with the other expedition’s members. He was, indeed, one of the men. What a heady experience!

Would the freedom and equality York had enjoyed for more than two years continue after the Corps of Discovery’s return? Sadly, no. It was York’s fate to return to a life of slavery. He was expected to meekly return to the role of subservient and loyal servant. William Clark and York never were friends. They were master and slave. They undoubtedly had genuine feelings for one another, but they were both products of their society. The expedition had changed their lives. It set Clark on a path and career that he followed for the rest of his life. That new course had tragic consequences for York. Alienation from his master and separation from his wife were two major events of York’s post-expedition life. York let Clark know that he believed he had earned his freedom. Clark disagreed, and York remained a slave for at least nine years after the expedition. Ultimately, York was given his freedom. Clark reported in 1832 that he gave York his freedom and set him up in a freight-hauling business with a wagon and team of horses. But York was a poor businessman, according to Clark, he lost the business, regretted being freed, and died in Tennessee while returning to his former master.

Was this York’s fate? There is another, happier ending to York’s story. This tale has York returning to the Rocky Mountains, where he lived a long, happy life as a chief among the Crow Indians. It would be nice to believe this, but the sad ending almost certainly was York’s fate. From the highs of exploring the West; of being treated as an equal, and even as someone special; having his “vote” count; to separation and alienation from his loved ones and long-time master, and death in an unmarked pauper’s grave, York’s life is a moving story. It is a wonderful example of how one man – an enslaved man – accomplished great things. Slavery did not rob York of his humanity and pride. A life of service and loyalty was leavened with the conviction and courage to stand up for what he believed.

Recognition of York is growing today. Appreciation for what he accomplished and for what he symbolizes is increasing. In January 2001, President Bill Clinton made York an honorary sergeant in the United States Army. Later that same year, in April 2001, York was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. York was individually honored at Thomas Jefferson’s home, Monticello, in January 2003 during the opening ceremonies of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial. A heroic-size bronze statue of York by nationally acclaimed sculptor Ed Hamilton looks out on the Ohio River and westward from the Louisville waterfront – a fitting honor to York by the city that he called home for most of his life. Actors portray York in first-person performances across the nation. A documentary film about him has been seen by thousands and another is in production. An opera has been staged. A two-hour public radio program has been aired. Books, articles, and poetry have been and are being written about him. And this is not all.

York’s life is a touching and very human story. It reveals the good and the bad of people and society. It contains life lessons that still apply today. If you should read about York, view a statue or artwork, or watch a documentary, think about York’s life. The good and the bad of it. The happiness and the sadness of it. We should rejoice in York’s triumphs, but also mourn his tragedies. May we learn from York and his life; and never let us forget this enslaved man who became an American hero.