Lewis and Clark at the Falls of the Ohio: A Timeline

By James J. Holmberg

Ca. March 1803 – William Clark (and George Rogers Clark) move across the Ohio River to Clarksville due to financial reverses in trying to help George. They share a house at Point of Rocks (later Clark’s Point) at the foot of the Falls. William sells Mulberry Hill to his brother Jonathan and his mill on Beargrass Creek to brother Edmund (both in May 1803). [George Rogers Clark writes William is settled at Clarksville in December 1802 in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, but other sources indicate and better verify March or April as the apparent time for his change in residence. There was a house that John Clark owned in Louisville (NW corner of Eighth and Jefferson) that was part of his estate in 1799. William might have stayed here when he was in Louisville or he might have stayed with various family members or friends.

June 19, 1803 – Meriwether Lewis in Washington writes William Clark [at Clarksville probably] a letter inviting him to join him as co-commander of an expedition to the Pacific Ocean via the Louisiana Territory and the Oregon Country.

July 18, 1803 – William Clark responds from Clarksville accepting the invitation. Requests that communications be sent/forwarded to Louisville. [This, together with Clark’s later known locations, indicates he essentially established himself in Louisville while preparing for the expedition and arranging his affairs.]

July 22, 1803 – Lewis in Pittsburgh writes to Thomas Jefferson. Direct further communication to him at Louisville.

July 24, 1803 – Clark in Louisville writes Lewis that he is arranging his affairs so they will not have to delay long “after you arrival here” and that he has temporally engaged some likely men for the expedition. That same day Clark writes Jefferson from Clarksville, in which he expresses his pleasure in accompanying Lewis on the expedition and requests that he forward his enclosed letter to Lewis on to him.

August 3, 1803 – Lewis in Pittsburgh writes to William Clark at Louisville. Refers to a possible interpreter that might “join us at Louisville.”

August 21, 1803 – Clark in Louisville writes to Lewis.

August 26, 1803 – Clark at Falls Ohio writes to John Conner. Clark tells Conner to “join us at this place.” [Falls was sometimes used instead of the town name. This was especially true for Louisville since writing from the Falls of the Ohio had for many years basically meant that one was writing from Louisville. Given that Lewis had requested Clark to have an interpreter (Conner) join them at Louisville, it is logical to conclude that this is where Clark wrote this letter from.]

September 3, 1803 – Clark in Louisville. Signs a document assigning his power of attorney to his brother Jonathan.

September 11, 1803 – Clark near Louisville writes to Lewis. [Clark may have been writing the letter from Jonathan Clark’s or William Croghan’s places or another family member’s or friend’s outside of Louisville. He may have located the letter “near Louisville” rather than use the estate’s name. In writing Jonathan he often addressed the letters to him “near Louisville.”

September 28, 1803 – Lewis in Cincinnati writes to Clark at Louisville.

October 14, 1803 – Meriwether Lewis arrives at Louisville. Report datelined Louisville, October 15, published in the November 1 edition of the Kentucky Gazette reports Lewis’s arrival at “this port” on October 14.

October 16 [15], 1803 – Thomas Rodney, Louisville to Caesar Rodney. Arrived in Louisville at 1:00 pm . . . “Captn. Lewis’s boat passed the Falls just before we got here but I am informed he will be detained here all next [week].” [In comparing this letter to Rodney’s journal, he apparently misdated the letter, actually writing it on October 15 but dating it October 16. This would also indicate that Lewis must have landed at Louisville and been there about a day before going through the Falls because people in Louisville already are aware that he will be detained “here” until next week. Rodney’s statement that Lewis’s boat “passed the Falls” would seem to indicate that the keelboat and pirogue were piloted through the Falls on October 15, the day after Lewis reached the Falls. Given the amount of time Clark spent in Louisville preparing for the expedition, arranging his affairs, and waiting for Lewis, it is logical to believe that he would have been awaiting his co-leader’s arrival in Louisville, and that they would have met there on October 14. The haste with which the boats were taken through the Falls is a bit unusual. This might be explained by river conditions which necessitated a quick passage in order to take advantage of higher water and consequently generally a safer passage, or other local conditions unknown. The general procedure would be to stay at Louisville until ready to actually proceed downriver. The resources (supplies, accommodations, etc.) needed – and in Lewis and Clark’s case the vast majority of family and friends as well – were in Louisville. If not taken through the Falls due to conditions, it must have been done to fit a plan Lewis and Clark had re: keeping the boat at Clarksville while they “delayed” for almost two weeks in Louisville and Clarksville wrapping up/preparing their affairs preparatory to heading down the Ohio and into the wilderness. Could the keelboat have been damaged in going through the Falls and this accounted for the delay?]

October 17, 1803 – Louisville. Thomas Rodney journal. Lewis and Clark visit him on his boat in the evening and take a glass of wine with him.

October 24, 1803 – Jonathan Clark’s diary. Notes that he was in Louisville and then Clarksville that day. He spent the night in Clarksville with William. [Why was Jonathan in Louisville and then Clarksville that day? Had Lewis and Clark planned on pushing off downriver from Clarksville on the 24th but were delayed for some reason? Contrary to what Rodney indicates, was the keelboat taken through the Falls on October 24th and Jonathan came into Louisville and went with the captains on the boat through the Falls? The time frame for taking the boat through the Falls just before setting out downriver would coincide well with the actual October 26th departure, but Rodney’s comment re: “Captn. Lewis’s boat” passing through the Falls on October 15 indicates that the boat went through the Falls on that date.]

October 26, 1803, Louisville. William Clark is at the Jefferson County courthouse to acknowledge the assignment of his power of attorney to Jonathan.

October 26, 1803, Clarksville. Jonathan Clark diary. Jonathan in Louisville and then in Clarksville. “Capt. Lewis and Capt. Wm. Clark sot [set] of[f] on a Western tour – went in their boat to Mr. Temple’s. [Benjamin Temple was Jonathan’s son-in-law who had a farm along the Ohio River in the area of present Lake Dreamland neighborhood in western Louisville.

October 29, 1803 – Report datelined Louisville published in the Kentucky Gazette of November 8 stating “Capt. Clark and Mr. Lewis left this place on Wednesday last [Oct. 26], on their expedition Westward.

1803-1806 – William Clark’s extant letters written during the expedition to family are to brother Jonathan and brother-in-law William Croghan, both living on estates near Louisville in Jefferson County. In addition, the artifacts (or “souvenirs”) sent back for family and friends and drafts/notes of William’s expedition manuscripts (field notes, reports, maps, etc.) were all sent to Jonathan’s care for dispersal and safekeeping.

August 20, 1806 – Clark writes Toussaint Charbonneau a letter offering his help to the interpreter, his wife Sacagawea, and their son Jean Baptiste. Charbonneau can find him at either St. Louis or Clarksville at the Falls of the Ohio this fall.

September 23, 1806 – The Lewis and Clark Expedition arrives in St. Louis, essentially ending the epic journey. Lewis and Clark collaborate on a letter to Jonathan reporting their successful return and reporting on the expedition since leaving the Mandan villages in April 1805. Since he will soon be with Jonathan can tell him more then. The letter is intended for publication and in a letter to Jonathan dated the following day, William reminds his brother to have it published. He also anticipates their arrival at the Falls about October 9 or 10 [they arrived November 5] and says they will remain in the neighborhood of Louisville for a few days.

September 23, 1806 – Lewis to Jefferson. Reports the expedition’s successful return. States their intended route east will be through Cahokia, Vincennes, Louisville, Crab Orchard, Ky., Abingdon, Va. . . . to Washington. Direct his mail to Louisville.

October 2, 1806 – The Frankfort Palladium prints the news that Lewis and Clark have returned! Will print more information when gets it.

October 9, 1806 – William’s letter to Jonathan is published in the Frankfort Palladium. It is the first detailed printed account of the return of the expedition. This report is reprinted in newspapers throughout the country and abroad.

October 10, 1806 – the members of the Corps of Discovery are discharged at St. Louis.

November 5, 1806 – Jonathan Clark’s diary. “Captains Lewis & Clark arrived at the Falls on their return from the Pacific Ocean after an absence of a little more than three years.” [Lewis and Clark and their party took the Cahokia to Vincennes route they had stated and then apparently continued overland to the Falls. That same day and over a number of succeeding days Clark is in the store of Fitzhugh and Rose in Louisville. During this time Lewis and Clark apparently spent most of their time in Louisville and at Trough Spring and Locust Grove, but probably were in Clarksville also.

November 8, 1806 – Jonathan Clark’s diary. Jonathan with Lewis and Clark at the Croghan’s Locust Grove estate for a family gathering and welcome home celebration.

November 9, 1806 – Lewis at Louisville writes secretary of War Henry Dearborn.

Ca. November 11, 1806 – Meriwether Lewis and most of the party, including two Indian delegations going to Washington, leave Louisville, traveling to Frankfort, and then separating and going by different routes – one overland due east through Lexington and the other (led by Lewis) southeastward through the Cumberland Gap and then down Virginia’s Great Valley.

December 14, 1806 – Clark, near Louisville [most likely from Trough Spring] to William Croghan. Will leave tomorrow for the eastward, stopping first at Col. Richard C. Anderson’s [east of Louisville] and taking the Wilderness Road via Danville.

Ca. December 15, 1806 – William Clark and most likely York leave the Louisville area for the East, traveling overland via the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap and down Virginia’s Great Valley.

Ca. April 1810 – Nicholas Biddle interviews William Clark re: the official expedition history (published in 1814). From these conversations, Biddle’s notes recorded that Lewis joined Clark who then resided at Louisville, and from Louisville, they proceeded by water to St. Louis; the party consisted of three groups of men, one of which was young Americans from the neighborhood of Louisville, they numbered nine and joined at Clarksville and/or Falls of the Ohio (York is listed separately as Clark’s servant); the original design of Lewis and Clark was to go up the Missouri in boats from Louisville after wintering at Charette (about 150 miles up the Missouri). [How accurate Biddle’s notes are and how accurate Clark’s recollections are cannot be fully determined. As written it is clear the facts are a bit incorrect based on the previously cited primary sources from the date of the events themselves. After Clark’s apparent statement that his and Lewis’s intent was to go up the Missouri from Louisville, Biddle bracketed in St. Louis, apparently assuming Clark meant to say it instead. This is not necessarily so. In Clark’s mind, he very well may have considered the start of the expedition to be Louisville (more correctly the Louisville area). His statement that he resided in Louisville is not completely correct, because we know he had moved across the river to Clarksville earlier that year. Given his brief residence in Clarksville after living in Louisville for eighteen years, he may not have considered Clarksville his home. This possibility is supported by an 1828 deposition Clark gave in which he stated he had lived in Louisville until 1803 at which time he was out of the country for three years. Regarding the men enlisted at the Falls, they were recruited in Louisville, most likely Clarksville, and by Lewis upriver. They most likely were actually enlisted at Clarksville and Louisville given their scattered dates of enlistment, thus referring to the Falls as the place of their enlistment.]

Sources

Donald Jackson, ed. The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978); William Clark Papers – Voorhis Memorial Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Mo.; The Kentucky Gazette, Lexington, Ky.; The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 43 no. 2, 1919; Dwight L. Smith and Ray Swick, eds. A Journey through the West: Thomas Rodney’s 1803 Journal from Delaware to the Mississippi Territory (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997); Jonathan Clark Diary, Clark-Hite Collection, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.; Jonathan Clark Papers – Temple Bodley Collection, The Filson Historical Society; Roy E. Appleman, Lewis and Clark: Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-1806) (Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975; second printing, St. Louis: The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation and Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association, 1993); Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

Source for Ambrose’s statement re: Lewis and Clark meeting in Clarksville

At the request of a number of people, I have prepared the following analysis regarding Stephen Ambrose’s statement in Undaunted Courage that Lewis and Clark met in Clarksville.

In Undaunted Courage, Stephen Ambrose recounts what the meeting of Lewis and Clark may have been like at Clarksville. The question has been asked, “Is this correct? Where did the captains meet? Clarksville or Louisville?”

Research has yielded the following information.

Ambrose writes on page 117:

“On October 14, he [Lewis] was at the head of the falls . . . At the foot of the rapids, on the north bank, was Clarksville, Indiana Territory. Louisville, Kentucky, was on the south bank. On October 15, Lewis hired local pilots, who took the boat and pirogues into the dangerous but passable passage on the north bank. [footnote 19] Safely through, Lewis tied up at Clarksville and set off to meet his partner, who was living with his older brother, George Rogers Clark.

When they shook hands, the Lewis and Clark Expedition began. . . .

Unfortunately, we don’t have a single word of description of the meeting of Lewis and Clark.“

A check of footnote nineteen reveals Roy Appleman’s Lewis and Clark [p. 52] as the source for Ambrose’s statement. Appleman writes:

“A key stopping point on the downriver trek was at the Falls of the Ohio. Beside their western end, on the south bank, was located Louisville, Ky.; and, on the north, Clarksville, Indiana Territory. . . . The best passage followed the north bank of the river. Lewis and his party arrived at the falls on October 14 [footnote 41]. Probably the next day, aided by local pilots, they took their boats through the dangerous channel and tied up at Clarksville. William Clark lived there with his older brother, George Rogers, and Lewis likely stayed with them. [footnote 42]. The reunion of the two younger men must have been a happy one.”

Appleman’s source for the information in footnote forty-one is the November 1, 1803 edition of the Kentucky Gazette. Footnote forty-two simply mentions that Lewis and Clark might have visited the Croghan’s at Locust Grove and Jonathan Clark or the other brothers [actually only one other brother] before leaving.

The November 1, 1803 edition of the Kentucky Gazette includes the report:

LOUISVILLE, October 15.

“Captain Lewis arrived at this port on Friday last [October 14] . . . he and captain Clark will start in a few days on their expedition to the Westward.”

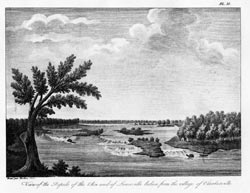

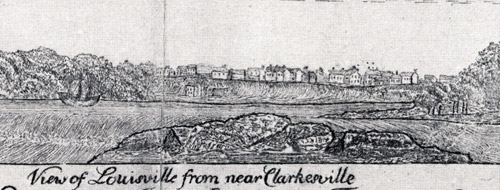

Those familiar with the geography of the Falls of the Ohio will immediately be aware of the incorrect statement that led to Appleman’s and consequently Ambrose’s assumption that Lewis traveled directly to Clarksville and met Clark there. That mistake is that Louisville is at the western end or foot of the falls, just as Clarksville is, right across the river from each other. The correct facts are that Louisville at that time was at the head of the falls, and that Clarksville was some two miles away at the foot. Those heading downriver would put into Louisville, hire a pilot, and then pass through the falls. Once through the falls they would put into Clarksville, the lower landing (the soon to be founded Shippingport), or travel immediately on their way.

Therefore, the report datelined Louisville means that Lewis did indeed put in there on October 14. Information from Rodney’s letter to his son indicates that Lewis and the keelboat and pirogue apparently passed through the falls the next day, October 15, and tied up at Clarksville. Lewis, therefore, would have been in Louisville for one day before passing through the falls.

In addition to making this error, which alters the story as Appleman, and consequently, Ambrose, recounts it, is them apparently being unaware of the facts of Clark’s activities and whereabouts that summer in preparing for and anticipating Lewis’s arrival at the Falls. The timeline/documentation establishes Lewis and Clark’s activities, whereabouts, and plans/intentions. Unless a new source comes to light that either confirms or contradicts the following conclusion, it must logically be concluded – supported by the known documents and facts – that Clark was waiting for Lewis in Louisville and met him there on October 14. The following day they had the boats taken through the falls to Clarksville, and then spent the next eleven days – including the day they left – in both towns before they pushed off from Clarksville on October 26.

The November 8, 1803 edition of the Kentucky Gazette reported:

LOUISVILLE, October 29.

“Capt. Clark and Mr. Lewis left this place on Wednesday last, on their expedition to the Westward.”

Wednesday last was October 26, and this place can be interpreted to mean the Falls area, rather than the more specific “port” that the October 15 article reported. It can also be interpreted literally, because Clark, and possibly Lewis, was in Louisville the day they set off downriver on the expedition.

This evidence demonstrates how intertwined Louisville and Clarksville are in the Lewis and Clark saga and what appropriate bookends they are for the Falls of the Ohio, the landmark that describes the whole area.

Sources

Donald Jackson, ed. The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978); William Clark Papers – Voorhis Memorial Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Mo.; The Kentucky Gazette, Lexington, Ky.; The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 43 no. 2, 1919; Dwight L. Smith and Ray Swick, eds. A Journey through the West: Thomas Rodney’s 1803 Journal from Delaware to the Mississippi Territory (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997); Jonathan Clark Diary, Clark-Hite Collection, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.; Jonathan Clark Papers – Temple Bodley Collection, The Filson Historical Society; Roy E. Appleman, Lewis and Clark: Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-1806) (Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975; second printing, St. Louis: The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation and Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association, 1993); Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

James J. Holmberg

The Filson Historical Society