Down the Ohio and Into the Wilderness: The Ohio River Journey of the Corps of Discovery

By: James J. Holmberg

“Left Pittsburgh this day at 11 o’clock with a party of 11 hands 7 of which are soldiers, a pilot and three young men on trail they having proposed to go with me throughout the voyage.”(1)

With those words, Meriwether Lewis began his first journal entry on his epic journey to the Pacific Ocean. Written on August 31, 1803, it was the first of what would be many entries that, together with the journal keeping of his co-commander William Clark and other members of their Corps of Discovery, would record their historic trek across the continent. The Corps’ two and one-half months on the Ohio was an important part of its journey. Often referred to as the recruitment phase of the expedition, it was that but also much more. The Ohio was where the all-important foundation – the nucleus – of the Corps of Discovery was formed. It was on the Ohio where Lewis and Clark met to actually form their partnership in discovery. It was on the Ohio that the famous Nine Young Men from Kentucky were recruited and enlisted. To these Nine must be added York, George Drouillard, and least two others who joined the expedition. While journeying down the Ohio these men began forming relationships and friendships and a dedication to their mission and to each other that would carry them through the dangers and hardships of their journey to the Pacific and back. Some of these men were also among the most important members of the Corps.

When Lewis finally left Pittsburgh, at least one month behind schedule, his destination was Louisville, Kentucky, where he would rendezvous with William Clark and the men he had recruited. The young explorer knew his friend and former army commander was coming with him. On June 19, he had written Clark inviting him to join the endeavor as co-commander. On July 5, he left Washington City for Pittsburgh, arriving there on July 15. And then he waited, and waited, for the keelboat he had ordered built to be completed because of the “unpardonable negligence and inattention of the boat-builders who . . . were a set of most incorrigible drunkards, and with whom, neither threats, intreaties nor any other mode of treatment which I could devise had any effect.” (2). Thus Lewis’s original estimated arrival date to rendezvous with Clark in Louisville grew later and later, from mid-August to late August to early October. He finally arrived on October 14. By August 3, Lewis had received Clark’s agreement to “chearfully join” him as co-leader and “partake of the dangers, difficulties, and fatigues,” as well as the “honors & rewards of the result of such an enterprise, should we be successful in accomplishing it.” (3).

While Lewis waited for the keelboat – which he christened the Discovery – to be finished he put together his temporary crew and took three young men on trial. Two of these recruits were still with him when he reached Cincinnati on September 28. They were most likely with him when he reached Louisville and are believed to be two of the nine men enlisted at the Falls of the Ohio (4). Clark, meanwhile, was recruiting men, and wrote Lewis on July 24, that he already had some of a “discription calculated to work & go thro’ those labours & fatigues which will be necessary.” Almost a month later, on August 21, Clark specified that he had retained four recruits and promised others an answer after consulting with Lewis (5).

Progress down the Ohio was slow. It had been a dry summer and the river was lower than anyone could remember it. By late summer and early fall, waterways were typically low. This was before the era of dams on rivers and navigation pools. Lewis’s progress down the Ohio was in the hands of mother nature and his own determination. Writing Clark on August 3, Lewis stated that he would make his way downriver even if he “should not be able to make greater speed than a boat’s length pr. day.” (6)

Lewis of course traveled at a faster pace than that, but sometimes the going was excruciatingly slow. Going past landmarks and towns that can still be visited today, Lewis and his little flotilla of keelboat, pirogue, and at least one canoe made their way downstream using the current, oars, poles, and sails. But the men also used more non-nautical means of pushing and pulling the boat over sand bars and through sections of extremely low water by using brute strength. When the obstacles proved too difficult Lewis hired oxen and horses from local farmers to drag the keelboat downstream (7). Within a week’s time, the boats had stopped at Bruno’s Island, where a visit and demonstration of the airgun almost ended in disaster when a bystander was grazed by an errant ball; passed McKee’s Rock; stopped at Steubenville, Ohio; passed Charlestown (present Wellsburg, West Virginia); and arrived at Wheeling. Lewis noted the dense fog that formed over the river, making visibility very low. These conditions also caused extremely heavy dews that resulted in such heavy condensation that water dripped from the trees as if it were raining (8).

Lewis arrived at Wheeling on September 7. He stayed two days, allowing the crew time to rest, do their laundry, and have bread baked. He also picked up supplies he had sent overland from Pittsburgh so that the keelboat would be lighter in the extremely shallow upper reaches of the Ohio and purchased another pirogue – the red pirogue that would travel over 3,000 miles on the journey. The young explorer almost recruited a doctor, William Patterson, the son of his Philadelphia tutor, Dr. Robert Patterson, but the young man failed to appear at the designated departure time, apparently deciding to pass on the western adventure. On the 8th Lewis dined with Thomas Rodney and party. They also were descending the Ohio, on their way to Mississippi Territory. That evening the travelers enjoyed watermelons onboard the Discovery (9). Another tasty dish Lewis enjoyed was squirrel. He twice commented on the squirrels migrating eastward across the Ohio and sending “my dog” into the river to “take as many each day as I had occation for, they wer fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasent food.” “My dog” is of course the famous Newfoundland Seaman, who accompanied Lewis on the entire expedition. He so endeared himself to the members of the Corps that he is referred to in the journals as “our dog.” Loyal to the end, there is good evidence that Seaman was with Lewis at the time of the latter’s death in 1809 and died on his master’s grave (10).

Lewis’s account of making his way downriver over the seemingly endless riffles and visits to towns soon ended. He described a visit to Grave Creek Mound, a major Indian burial mound below Wheeling, as well as a stop at Marietta. But four days after leaving Marietta and routinely recording the towns, river conditions, and distances traveled Lewis abruptly discontinued his Eastern Journal. The last entry is dated September 18. Why he stopped keeping the journal isn’t known. From September 18 to the Corps arrival at Fort Massac on the lower Ohio on November 11, there is a gap. It is most unfortunate that there is not a daily log of what happened during this time. Much must be pieced together from other sources, some must be deduced from the evidence, and some facts remain a mystery. Information regarding Lewis’s visits at Maysville and Cincinnati; his stop at Big Bone Lick for specimens for President Jefferson; his arrival at Louisville and meeting with Clark; his estimate of the men Clark had recruited; the Corps’ thirteen day stay at the Falls of the Ohio and why it was delayed there that long; the departure from Clarksville; and the other towns the explorers visited between the Falls and Fort Massac all remain fragmentary or unknown to this day. So much more would be known if Lewis had maintained his journal or if Clark had begun a journal upon leaving the Falls. This foreshadowed Lewis’s journal keeping practices on the expedition – gaps for weeks and months at a time – but was uncharacteristic of Clark, who rather faithfully kept a journal or memorandum book while on trips.

What we do know is that Lewis continued downriver with his little flotilla. The lower he descended the more navigable the Ohio became, but it was still very low. About September 23 he arrived at Maysville and on the 28th Cincinnati. Lewis spent a week at the future Queen City, resting the men, visiting old friends, learning about and viewing animal bones and fossils from Big Bone Lick courtesy of Dr. William Goforth, and writing to Jefferson and Clark. On October 1, he dispatched the boats to Big Bone Lick, and then followed himself three days later via land. Lewis noted in his letter of October 3 to the President that the low water would require the keelboat three days to travel the fifty-three river miles to the lick, while he would spend less than a day going the seventeen land miles. Several days were apparently spent at Big Bone Lick in collecting specimens for Jefferson. Unfortunately, they never made it to him. The following year, sitting in crates on a boat at the Natchez dock, they sank in the Mississippi River (11).

As the days grew shorter and cooler, William Clark must have worn a path to the Louisville landing. He probably had received Lewis’s letter of September 28, predicting his arrival before the letter’s, about October 6 or so. The keelboat could be expected to hove into sight at any moment. Since receiving his friend’s invitation on July 17, Clark had devoted his time, energy, and abilities to preparing for the expedition. Lewis’s delay in reaching Louisville probably only served to heighten not only Clark’s but the recruits’ and the area residents’ anticipation. Finally, on October 14, Lewis arrived! Clark, who had spent most of the summer in Louisville preparing for the journey, almost certainly was there to greet his partner in discovery. A study of their correspondence that summer clearly establishes their intention to meet in Louisville. It is scarcely credible to think that he would not have been keeping a close watch upstream and at the landing for his friend. Eminent Lewis and Clark historian Donald Jackson believed so, writing in Thomas Jefferson and the Stony Mountains that “Clark met Lewis joyfully at Louisville.” (12)

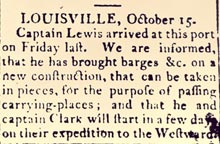

The October 15 edition of the Louisville Farmer’s Library newspaper reported Lewis’s arrival the day before. The report was reprinted by the Lexington Kentucky Gazette and it is this source that survives today. “LOUISVILLE . . . Captain Lewis arrived at this port on [October 14] . . . he and captain Clark will start in a few days on their expedition to the Westward.” More than a few days passed, however, before the foundation of the Corps began their journey west. It wasn’t until October 26, thirteen days after Lewis’s arrival, that they left (13).

Why the delay? A few days became a week and a week became almost two weeks. Did something happen to the keelboat in going through the Falls? Thomas Rodney went through the Falls three days after Lewis and Clark in a bateau with less than half the draft of the Discovery. He described a terrifying trip navigating through the churning, rock-strewn channel – even with James Patten, the Falls’ most experienced pilot, guiding the craft (14). Did William Clark perhaps suffer a bout of illness? Soon after leaving, Clark fell ill not once, but twice. It’s possible, but he doesn’t reference his illness on the Ohio and Mississippi as being relapses of an earlier malady (15). Perhaps more time to evaluate and enlist the recruits? That’s unlikely. Clark had enlisted three – “the best woodsmen & Hunters, of young men in this part of the Countrey” – by the time Lewis arrived, and the other “Nine Young Men from Kentucky” were enlisted from October 15 to October 20 (16). Was the delay another of Lewis’s emerging trends of procrastinating or staying somewhere longer than he stated he intended? Maybe one day we’ll know.

While at the Falls of the Ohio Lewis and Clark are known to have spent their time enlisting the other six members of the “Nine Young Men,” making other preparations, and visiting. From their base camp at Clarksville, the captains went back and forth between the Clark farm and Louisville. On the evening of October 17 they visited Rodney on his boat tied up at the Louisville waterfront and enjoyed a glass of wine with him (17). They most likely ventured out to Jonathan Clark’s Trough Spring estate and to Locust Grove, home of Clark’s sister and brother-in-law, Lucy and William Croghan. October 24 might have been planned as the day of departure for the nucleus of the Corps. If so, something happened to delay the explorers another two days. On the 24th, Jonathan went into Louisville and then on to Clarksville. He spent the night there with William Clark but then went back across the river to Louisville and spent the night of the 25th there. On the 26th, William was in Louisville at the Jefferson County Court House to file legal papers. Perhaps the Clark brothers – and maybe Lewis – left Louisville together for the lower landing at the foot of the Falls and then across the river to Clarksville on that famous day. By mid-afternoon, the time to leave had come. Keelboat and pirogue loaded, the men aboard, and final goodbyes said, the foundation of the Corps of Discovery pushed off down the Ohio on their journey to the Pacific. Tears undoubtedly were shed and arms frantically waved in farewell. Jonathan wasn’t quite ready to part with his brother. He boarded the keelboat and went about ten miles downstream with the Corps as they “set off on a western tour.” (18).

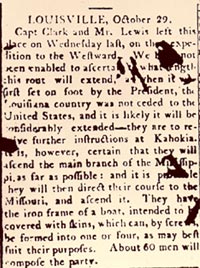

The October 29 issue of the Farmer’s Library carried news of the departure that was picked up by the Lexington Kentucky Gazette. “LOUISVILLE . . . Capt. Clark and Mr. Lewis left this place on Wednesday last [October 26], on their expedition to the Westward,” it reported. The article then speculated about their ultimate destination possibly being the Missouri River, the final size of the party, and the innovative iron frame boat (19).

Information is almost nonexistent for the Corps’ trip from the Falls to Fort Massac. Jonathan Clark makes mention of parting with the explorers at his son-in-law’s farm in present west Louisville and Lewis mentions stopping at the first Kentucky settlement below Louisville (20). That settlement might have been West Point, at the mouth of Salt River, where John Shields lived. The Ohio was still low, and the channels meandered from one side of the river to the other, as the boats made their way past islands, rocks, and sandbars. With the additional manpower of the “Nine Young Men” and York steady progress was made. The scenery must have been beautiful that time of year, with fall colors spread across the forests lining the banks. The Corps probably took advantage of any settlements they encountered. Contemporary accounts describe the Kentucky side of the river as being dotted with farms and small settlements and the Indiana side as being wilderness and Indian country. Yellow Banks – now Owensboro – and Henderson – also known as Red Banks – where Clark associate Samuel Hopkins lived, might have been stops. The mouths of many creeks and rivers were passed. The Salt, Blue, Wabash, Green, Tradewater, Cumberland, and Tennessee were just some of the Ohio’s tributaries they passed. This was familiar territory for some, if not most, of the men. William Clark, and almost certainly York, had boated down the Ohio several times.

On November 11, the little flotilla arrived at Fort Massac. Here, Lewis had arranged to rendezvous with a detachment of soldiers from South West Point, Tennessee. They were not there and Lewis and Clark hired a civilian to go get them. That person was George Drouillard. Of Shawnee and French-Canadian parentage, Drouillard became one of the most important members of the Corps of Discovery. Living at Massac Village west of the fort as well as across the Mississippi River at Cape Girardeau, Drouillard was hired by the captains as an interpreter and hunter. He did important service as both. If the captains had an important or dangerous mission, Drouillard almost invariably was called on to help achieve it. Other recruits were also acquired at Fort Massac. More manpower was needed for the upcoming segment of the journey. Not only were some or all of the temporary crew who had helped bring the boats down the Ohio turning back at Massac but once the Corps entered the Mississippi it would be sailing against the current. Clark stated that “we Calld for a detachment of 14 men from that garrison to accompany us as far as Kaskaskees . . .” How many of these soldiers joined the permanent party isn’t known. At least two and perhaps more were drawn from Massac (21).

It was at Fort Massac on November 11, that Lewis briefly began keeping his journal again. Two days after arriving at the post, the explorers left for the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi – just a short distance away. On the evening of November 14, the Corps arrived there. The explorers spent five days at the confluence, investigating the area, visiting residents – both red and white, and beginning their scientific endeavors. On November 20, the Corps began its ascent of the Mississippi River.

The first major stretch of the Corps of Discovery’s journey had been accomplished. Some 1,000 miles and two and one-half months lay behind them. In mid-November of 1803, the explorers were only on the threshold of their adventure. Some 8,000 miles and three years still lay ahead for them. The vast country up the Missouri and west of the Rockies still beckoned. But before then these dauntless men still faced completing the formation of the Corps and their first winter encampment.

Much had been accomplished on this stretch of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The descent of the Ohio was an all-important part of the journey. From the keelboat being built at Pittsburgh, to Lewis and Clark meeting to form one of the most famous partnerships in history, to the recruitment and enlistment of the crucial foundation of the Corps, this American odyssey had been successfully launched toward success and fame on the waters of the Ohio River.

FOOTNOTES

- Gary E. Moulton, editor, The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:65.

- Donald Jackson, editor, The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with related Documents, 2 vols., revised edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:125.

- Jackson, 1:110. Lewis’s invitation to Clark to join him on the Expedition had arrived at a perfect time in Clark’s life. He had impoverished himself trying to help his brother George Rogers Clark with his legal and financial difficulties. Only months earlier he had sold his farm Mulberry Hill outside Louisville (that he and York had called home since coming to Kentucky in 1785) and moved across the Ohio River to Clarksville to get a fresh start.

- Jackson, 1: 125. Who those recruits were are not definitely known yet today. It is generally agreed that George Shannon was one of the them. About eighteen years old, he had been attending school in Pittsburgh, and probably joined the expedition there. The other recruit is more uncertain. John Colter is usually named as that second recruit, joining Lewis at Maysville, Kentucky, when Lewis stopped there about September 24. A more likely possibility might be George Gibson. A native of Mercer County, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, Gibson identified himself after the expedition as a resident of Mercer County, therefore signifying that as his likely home when he left on the western journey. Another piece of evidence, that might be nothing more than coincidence but that must be considered, is that Gibson and Shannon both have the same enlistment date, October 19. This would have given Clark time to evaluate them and give his okay to enlisting them in the enterprise.

The Falls of the Ohio was an approximate two mile stretch of rapids through three channels. In times of high water they could be navigated without great danger or difficulty but as the water dropped they could become more dangerous. The best channel was the northern one, called the Indian (later Indiana) Chute, along the Indiana shore. Louisville was founded in 1778 at the head of the Falls on the Kentucky side of the river. Clarksville was founded in 1783 at the foot of the Falls on the Indiana side. By 1803 Louisville was a major western town, growing rapidly, with a population of some 600, with thousands more in surrounding Jefferson County. Clarksville remained a small village, plagued by floods, and surpassed by Jeffersonville to its east and New Albany to its west after their founding in the early 1800s. - Jackson, 1: 113, 117. Clark is believed to have had seven recruits waiting for Lewis. They were Joseph and Reubin Field, Charles Floyd, Nathaniel Hale Pryor, John Shields, William Bratton, and perhaps John Colter. Colter would be one of the recruits if Gibson was indeed already with Lewis. Three of the four that Clark mentioned as already recruited are known: the Field brothers and Floyd. Their enlistment date of August 1 is two and one-half months before Lewis arrived at the Falls and inspected potential Corps members. Who the fourth was can only be speculated. Colter, who has an enlistment date of October 15, the earliest after that for the Field brothers and Floyd is a good candidate. Nathaniel Pryor was Floyd’s first cousin, and like his cousin, was appointed a sergeant in the Corps. His enlistment date was October 20 but if one of the four there might have been a reason for the delay. The fact that two of the three Corps’ sergeants came from the Nine Young Men testifies to the quality of man that Clark recruited. Was it John Shields? Although married, Clark made an exception to Lewis’s instruction to recruit unmarried men, knowing that Shields’ skills as a blacksmith, gunsmith, and hunter were crucial needs of the Expedition. His enlistment date was October 19. William Bratton? He might have been one of those likely young men that applied to Clark, perhaps venturing northward from south central Kentucky upon hearing about the Expedition. His enlistment date was October 20. A final possibility is Clark’s enslaved African American, York, but it is unlikely that Clark would have counted his servant as one of the recruits. In some ways, he was a nonperson, someone to be there to take care of the needs of his master, but not worthy of notice, and certainly not in an official capacity as an expedition recruit. York would go on the entire journey, becoming the first African American to cross the United States from coast to coast, but never be carried on the rolls as an official member nor be compensated. Any reward for his loyal and important service would have to come from his master. It is not known if Clark rewarded him. It is also possible that none of these men were the fourth recruit, he not going for some reason on the Expedition.

- Jackson, 1:116.

- Moulton, 2:67-74.

- Moulton, 2:67.

- Moulton, 2:74-75. For Thomas Rodney’s account of his trip down the Ohio and encounters with Lewis, as well as with Clark once he reached Louisville, see the published journal of his trip entitled A Journey through the West, edited by Dwight L. Smith and Ray Swick (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997). Also of interest are Rodney’s letters written to his son on the journey published in 1919 in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (vol. 43).

- Moulton, 2:79, 82; James J. Holmberg, “Seaman’s Fate?” We Proceeded On, vol. 26, no. 1 (February 2000), pp. 7-9.

- Jackson, 1:126-132.

- The quote appears on p. 145. There is confusion regarding where Lewis and Clark met to actually form their famous partnership. Was it Louisville or Clarksville? The great weight of evidence places the meeting in Louisville. It was in Louisville that Clark was spending much of his time preparing and recruiting for the expedition and wrapping up his affairs. His family and friends lived in and around Louisville and he spent time with them as well. Their correspondence clearly states their intention to join forces in Louisville. How is it then that Clarksville is sometimes cited as the meeting place? The basis for it seems to be a geographical error made by Roy Appleman in his Lewis & Clark: Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-1806). Appleman placed Louisville at the foot of the Falls of the Ohio, directly across the river from Clarksville, instead of at the head of the Falls where it actually was in 1803 (later growth resulted in it stretching downstream to well below the Falls). When Lewis reached the Falls, Appleman assumed he went through the Falls in order to reach either town. Since Clark had moved across the river to Clarksville earlier in 1803 he believed it was a simple matter of taking a right to Clarksville instead of a left to Louisville and then going in search of his partner (see Appleman, p. 52). Later writers, including Stephen Ambrose, have relied on Appleman as their source for the explorers’ meeting and this error continues to be perpetuated today.

- (Lexington) Kentucky Gazette, November 1 and 8, 1803. No issues of the Farmer’s Library from those dates are known to be extant. During that time period the Farmer’s Library was published on Saturdays which corresponds to the date of the reports picked up by the Gazette. Both papers were weeklies, as were most newspapers at that time.

- Smith and Swick, pp. 124-25. James Patten was one of Louisville’s original settlers. He was also the former father-in-law of Nathaniel Hale Pryor. His daughter Peggy married Pryor in 1798 but is believed to have been dead by the fall of 1803.

- James J. Holmberg, editor, Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark, with a Foreword by James P. Ronda (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), pp. 60, 64-65n.

- Jackson, 1:117.

- Smith and Swick, p. 124.

- Jonathan Clark Diary, October 24-26, 1803, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.; William Clark Power of Attorney, Jonathan Clark Papers – Temple Bodley Collection, The Filson Historical Society; Holmberg, p. 64n.

- Kentucky Gazette, November 8, 1803.

- Moulton, 2:108. Lewis noted in his journal for November 23, 1803, while at Louis Lorimier’s at Cape Girardeau, that a very pretty girl there was “much the most descent looking feemale I have seen since I left the settlement in Kentuckey a little below Louisville.”

- Holmberg, pp. 60, 66-67n, 69n. South West Point was on the Tennessee River at Kingston, west of Knoxville. Why Lewis had requested troops from a post in that area when he would be passing two others on the way west was apparently a result of what he intended his original route to be – through Tennessee to Nashville and then down the Cumberland River to the Ohio. He states as much in his April 20, 1803 letter to Jefferson (see Jackson, 1:38). Lewis’s plan was to have a keelboat built at Nashville and man it with a detachment from the garrison at South West Point. Having the keelboat built at Nashville changed to having it built at Pittsburgh, but the plan to detail men from South West Point remained.

The two Fort Massac soldiers indicated by records to have joined the permanent party were Joseph Whitehouse and John Newman. Whitehouse accompanied the Corps on the entire Expedition but Newman did not, being court-martialed in the fall of 1804 and sent back from Fort Mandan with the temporary party and keelboat in the spring of 1805. See Holmberg, pp. 67n and 69n for further speculation regarding this detachment.